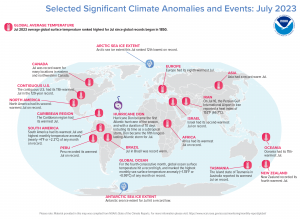

July 2023 was the hottest ever globally, surpassing all temperatures since global records began in 1850. Image Source: NOAA

With 2023 to be the hottest year on record, find out how can architects and designers create safer designs that will withstand hotter climate.

— Formaspace

AUSTIN, TEXAS, UNITED STATES, September 21, 2023 /EINPresswire.com/ — 2023 Is The Hottest Year On Record

We don’t have to tell you it’s been hot.

July’s heat was extreme, beating all heat records recorded since 1850, and 2023, as a whole, is on track to be the hottest year ever.

It’s also been a year of weather-related disasters, with unprecedented flooding events in Vermont and other states and the tragic loss of life due to fatal fires wiping out communities in Hawai’i, Greece, British Columbia, and Washington state.

Along with the prolonged heat comes the risk of power outages and potentially lethal heat-related conditions, such as heat stroke.

The question for architects and designers is how should we respond.

How can we meet these mounting challenges by creating new designs for the built environment that provide safer, more resilient shelters capable of withstanding a hotter, more active climate?

Inspiration From The Past: Historic Vernacular Designs That Beat The Heat

Seeking inspiration for some cool building design thinking, we remembered a book in our library – Cool Homes in Hot Places by Suzanne Trocmé with photos by Andrew Wood.

Published in 2006, this book features a series of high-end residential architecture case studies that consider the effect of hot climates on suitable terrain, materials, color, and furnishings choices.

What struck us in re-reading the book is how many of the approaches for responding to warm climates are inspired by traditional – if not ancient – design features, which we thought would be interesting to explore further in this article because they are not only applicable to high-end residential construction, but also for school, office, healthcare, laboratory, and industrial facilities as well.

Ancient Architectural Features That Keep Building Interiors Cooler

Passive cooling may have become a current buzzword in the A&D community, but in many ancient Middle Eastern communities, the tradition of keeping cool in hot climates is thousands of years old.

Let’s look at some of the passive cooling features that have been in use for millennia in these regions.

· Bâgdir (Windcatcher) Cooling System

The first is a tall chimney design with vertical slats, known as Bâgdir, which roughly translates as ‘windcatcher’ in English.

The city most associated with these passive cooling towers is the historic city of Yazd in Iran, which has very hot and dry summer seasons. The tall chimneys draw the hot air upward, and prevailing winds sweep it away, keeping the building below cool – without fans or electricity.

· Ventilated Domes That Draw Heat Up And Out

Ventilated domes are another feature of traditional architecture that dates back thousands of years, with examples found in the Middle East, Africa, and India.

Heat naturally rises inside buildings; adding an opening at the top can help create a passive chimney effect to draw the warm air out. Creating a curved surface, such as the famous onion domes of Islamic architecture, can help improve air circulation further, drawing additional heat from the building interior below.

· Chinese Skywells Help Moderate High Temperatures

Many regions of China can be hot and humid much of the year.

To manage the heat, many traditional homes in the south and eastern parts of China have “skywells” or lightshafts, known as “tian jing” (天井). These open areas often feature a masonry wall that stays cool in the shade; the opening in the roof allows hot air to escape from the interior of the building.

· Qanat – Aqueduct Cooling Systems

Another historic design feature for cooling the built environment relies on the presence of gently sloping aqueducts built in tunnels deep underground.

Known as a Qanat in Persian, these traditional systems are still in use today to transport water long distances.

In addition to supplying water, the underground Qanat can be connected via ventilation shafts to the basements of buildings equipped with a Bâgdir windcatcher tower above. In this system, the cool underground air flowing around the water is drawn up by the chimney effect.

(As we’ll discuss later, modern engineers in Seville, Spain, are revisiting the idea of cooling today’s neighborhoods with Qanat-style aqueducts.)

Ancient engineers were also able to use the cooling effects of Qanats to keep ice, even during the extremes of the desert heat, by storing the ice in yakhchals, a highly-insulated masonry dome.

· Traditional Orsi Windows In Iran And Lattice Building Designs In India

When we think about windows in the west, we immediately think of expansive openings fitted with clear window glazing. But building designers from centuries ago looked at window openings differently.

In Middle Eastern regions, such as Iran, windows were often smaller, inset from exposure to direct sunlight, and often fitted with intricate geometric designs, known as Orsi windows.

In other cases, they built what we might call an oriel, bay, or box window, that projects outside of the building’s façade. Known as a mashrabiya in Arabic, these protruding window structures can capture any prevailing breezes and allow hot air to exit. To keep the sun’s rays at bay, traditional mashrabiya are covered in intricate wood-carved designs.

In other regions, such as India, expansive window openings were traditionally fitted with intricate lattice designs, allowing the prevailing breeze to pass through while providing some privacy and shade protection from direct sunlight entering the building.

The Influence Of Traditional, Islamic-Inspired Spanish And Portuguese Colonial Architecture

Julia Solodovnikova

Formaspace

+1 800-251-1505

email us here

Visit us on social media:

Facebook

Twitter

LinkedIn

![]()

Originally published at https://www.einpresswire.com/article/656959007/traditional-architectural-design-features-that-beat-the-heat